Modern life gives us much more freedom to be authentic in our lives, relationships, and love. The freedom to be authentic with yourself is great. However, it is also challenging; the feeling of authenticity can hurt.

What Authenticity in Love Entails

Cultural values of modern life encourage us to live authentically. This means being sincere and honest with yourself and with others. This also means taking responsibility for your mistakes.

In her book Why Love Hurts, sociologist Eva Illouz explains what “authenticity” means and what it entails when we live our love lives according to it. Not many of us have escaped the pain of intimate relationships. Love and relationships can be happy. However, they can take many different forms, such as loving someone who refuses to commit to us or experiencing heartbreak when a lover leaves us. Finding love can be a challenging and frequently painful experience in a number of ways, such as feeling bored in a relationship that is far less than we had anticipated or returning from bars, parties, or blind dates alone.

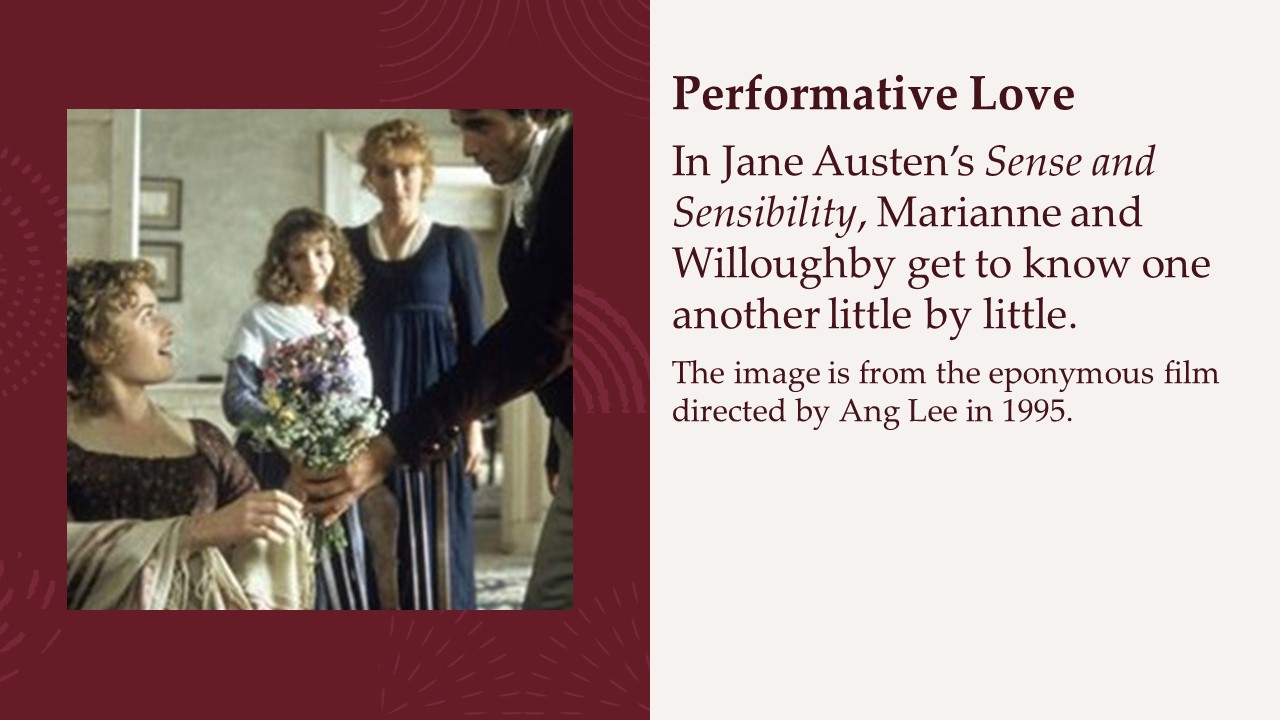

Performative Love and Relationships of the Past

In the past, men were usually more experienced in sentimental or sexual relationships than young women of marriable age. The declaration and expression of feelings could be an overwhelming experience for a young woman who, overcome by new emotions, could do or say something inappropriate. Courtship, therefore, was a process that had to be monitored and supervised.

A couple of centuries ago, courtship advanced step by step. Couples were allowed to speak to one another supervised, then alone, then they could spend some time alone and keep each other company. By that time, their mutual interest had been made explicit. Illouz calls this model “regime of performativity of emotions,” indicating that courtship, more than a spontaneous endeavor, was a regulated and ritualistic practice.

One of the most interesting aspects of “old” courtship was that emotions could be induced by the expression of sentiments. Feelings could be first declared and expressed, and consequently, felt. In other words, a man could induce feelings in a young woman by enacting a process of courtship that was ritualistic, regulated, and aimed at developing the appropriate – emotional as well as verbal – response in a partner. As Illouz explains, courtship was:

An incremental process, often induced by another’s use of appropriate signs and codes of love. It is the result of a subtle exchange of signs and signals shared by two people. In such a regime, one of the two parties took on the social role of inducing the emotions of the other, and this role fell on the man. In a performative regime of emotions, the woman was not and perhaps could not be overwhelmed by the object of love; courtship followed rules of engagement such that the woman was drawn in a close and intense bond progressively. She responded to signs of emotions whose patterns of expression were well rehearsed.

(Why Love Hurts, 30)

Performative Love and Relationships of the Modern Era

This older set of practices is opposed to the contemporary regime of “emotional authenticity,” which characterizes modern-day romantic relationships. I will summarize both systems below. The reader may decide which is preferable.

Today’s “authenticity” implies self-knowledge, honesty, and constant scrutiny. What we ordinarily call “freedom” is the freedom to fall in love with whomever we please, as well as the freedom to declare our feelings to him/her, ourselves, and others. It is, in truth, a complex regime of rules and practices that places a significant amount of pressure on individuals: the pressure to know themselves, to know what they want, and to act accordingly:

Authenticity demands that actors know their feelings; that they act on such feelings, which must then be the actual building blocks of a relationship; that people reveal their feelings to themselves (and preferably to others as well); and that they make decisions about relationships and commit themselves based on these feelings. A regime of emotional authenticity makes people scrutinize their own and another’s emotions in order to decide on the importance, intensity, and future significance of the relationship.

(Why Love Hurts, 31)

Later in her study, Illouz further explains that the set of practices that regulate the contemporary regime of romantic relationships belong to a world in which individuals must rely exclusively upon themselves to understand the true nature of their feelings towards someone else: is it love? Is it mere sexual attraction? The choice of a partner, therefore, is the result of a complex assessment that every individual is expected to be able to perform.

Authenticity versus Performativity: What Is Different?

Readers will surely have noticed that in the passage between the two systems, courtship has become increasingly private and less of a collective process. In the past, young women were expected to go through the process of courtship from a position of authority within familial protective relations, who would assist them in the process.

Today, choosing a partner is a fundamentally individual and private matter. As everyone is free to make their own choices, everyone is also exposed to high doses of isolation and self-doubt, a typical contemporary condition belonging to all who decide to exert full agency and assume complete responsibility in matters of the heart.

I recently published an article in University of Florence Press in which I argue that A Room with a View (1908) by English writer E.M. Forster is one of the first modern romantic novels to show the rise of authentic love.

In my other article in The Diversity of Love Journal, I suggest that E.M. Forster’s A Room with a View (1908) is one of the earliest examples of a modern romantic novel that showcases the rise of authenticity in courtship. The article describes how the novel illustrates the transition from performative love to authentic love.

References

Illouz, E. (2012). Why love hurts: A sociological explanation. Polity.