Anthropologist Charles Lindholm (2006) writes about romantic love as a yearning for the sacred. According to philosopher Irving Singer (1984), romantic love is a combination of various aspects of love, ranging from the libidinal to the ideal.

The mixture of sex and the sacred, which Singer (1984) calls the “holy oneness” of love, is perhaps the key to the definition of romantic love. A symbol of love can convey multiple meanings and sentiments associated with love; some can be contradictory (Turner, 1967).

I have argued elsewhere against dissecting and ranking the types of love. Instead, I see romantic love as both sexual and divine (Skoggard, 2018). Furthermore, romantic love is a sentiment that is shared by people in many cultures (Jankowiak & Fischer, 1992; Karandashev, 2019).

Canadian anthropologist Wilson Duff has written about the combined elements of sex and sacredness in Northwest Coast art. Let’s consider his ideas and observations.

Wilson Duff Studied People Living on Vancouver Island, Canada

Wilson Duff (1925–1976) was a great Canadian archaeologist and cultural anthropologist. He was known for his research on First Nations cultures of the Northwest Coast of Canada, such as the Tsimshian, Gitxsan, and Haida, and especially for his interest in their plastic arts.

Duff was born 1925 in Vancouver, British Columbia. He received a Master Degree from the University of Washington and did his fieldwork (1949-1950) among the Cowichan, a Coast Salish people living on Vancouver Island. He was the curator of anthropology at the British Columbia Provincial Museum in Victoria, B.C. from 1950 to 1965.

Duff was an early advocate for First Nation rights and presented First Nation peoples’ input in the curation of museum collections and exhibitions. His great interest was Northwest Coast art, which he promoted as fine art.

“Nothing Only Comes in Pieces,” But an Art Object Is a Part of a Bigger Story and Meaning

In his writings, he advocated and encouraged a deeper interpretation of the art beyond a description of form and function. He had a famous saying that “nothing only comes in pieces.”

Art objects, according to Duff, are part of a larger story and meaning. While scholars interpreted the art images of Northwest Coast America in terms of totemic crests, spirit creatures, or purely aesthetic objects, Duff saw in those art images something deeper. He believed that the art invoked the taboo realms of sex and the sacred.

Sexual Meanings in Northwest Coast Native American Art

For Duff the raven’s beak, or mouth of a toad, were more than a beak and mouth.

According to Duff, the wooden dish of a raven with its concave back and protruding beak is what he called a “vulvic-phallic image.”

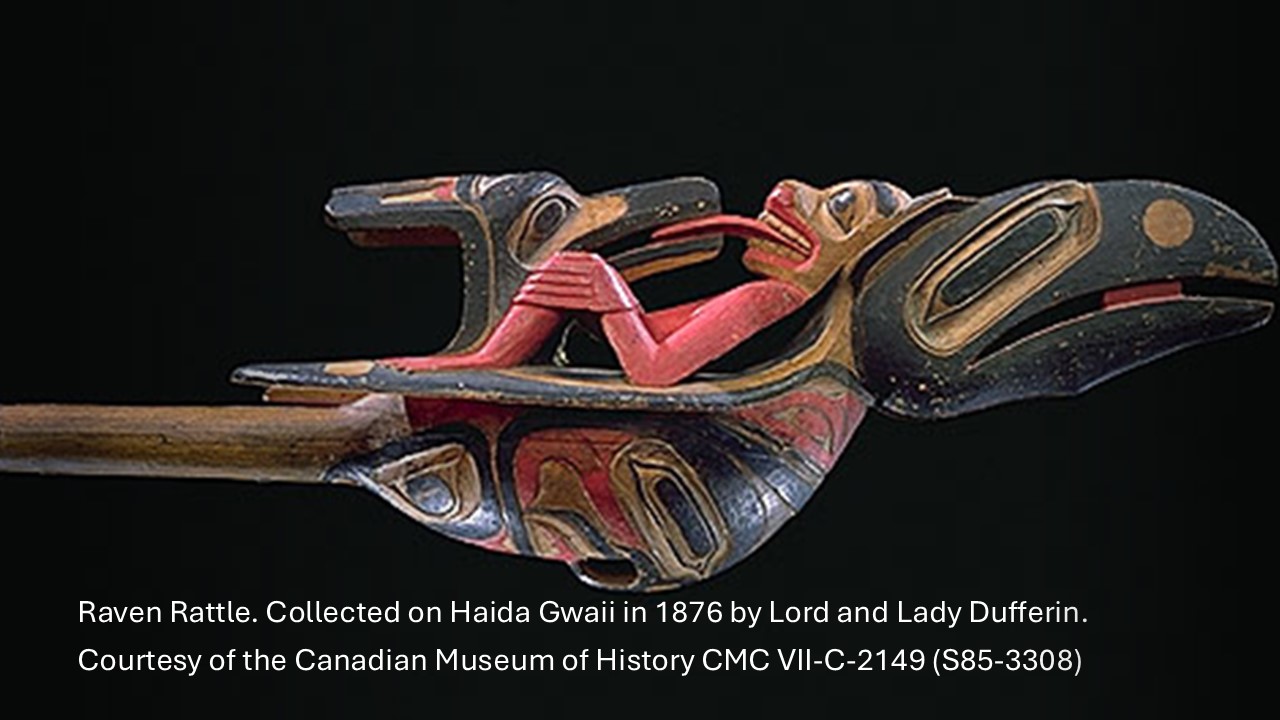

The Northwest Coast raven rattle (see figure above) is a more explicit depiction of the sex act:

A human figure with legs spread apart and a tongue entwined with another bird’s.

Why Is the Totem Pole at the Entrance of a Lodge a Vulvic-Phallic Symbol?

Wilson Duff also considered the totem pole at the entrance of a lodge a vulvic-phallic symbol, the vulvic part being the doorway onto the lodge, which is the home of the descent group.

I would argue that this is an example of extending the unifying sentiments of the love act to all the building’s occupants. The lodge is seen as the womb of the extended family, in which sentiments of love are shared. The totem pole is another vulvic-phallic symbol that invokes and extends the ontological state of sexual love to encompass and unify the larger group.

Sex and the Sacred

Wilson Duff was ridiculed for having a one-track mind seeing sex in much of Northwest Coast art (Fisher, 2022). However, he was not alone.

Other anthropologists also perceive sexual imagery in cultural artifacts they study (see my other article in this journal, “How the Australian Bullroarer Invokes the Happiness of Sexual Love“).

Theologian Charles Williams writes about the deeply profound sentiments of romantic love as both sexual and divine:

There is no other human experience, except Death, which so enters into the life of the body; there is no other human experience which so binds the body to another being. The central experience of sanctity is to be so bound to another, though for the saints this other is God. But what of the Lover if love is also God? (Williams, 2005, p. 24)

You can learn more about cultural symbols of love and sex from Ian Skoggard’s video talk on “Representations of the Love Act across Cultures”

References

Duff, W. (1981). The world is as sharp as a knife: Meaning in Northwest Coast art. In D. N. Abbot (Ed.), The world is as sharp as a knife: An anthology in honour of Wilson Duff (pp. 209-224). British Columbia Provincial Museum.

Fischer, R. (2022). Wilson Duff coming back: A life. Harbour Publishing Co., Ltd.

Jankowiak, W. R. & Fischer, E. F. (1992). A Cross-Cultural Perspective on Romantic Love. Ethnology 31(2), 149-155. https://doi.org/10.2307/3773618

Karandashev, V. (2019). Cross-cultural perspectives on the experience and expression of love. Springer.

Lindholm, C. (2006). Romantic love and anthropology. Etnofoor, 19(1), 5-21.

Singer, I. (1984). The nature of love, Vol. 2 – Courtly and romantic. University of Chicago Press.

Skoggard, I. (2018). Love lost and found: A sentimental history of American medical missionaries in China, 1905-1951. In L. Carspecken (Ed.), Love in a time of ethnography: Essays on connection as a focus and basis for research (pp. 81-100). Lexington Books.

Turner, V. (1967). The forest of symbols: Aspects of Ndembu ritual. Cornell University Press.

Williams, C. (2005). Outlines of romantic theology. Apocryphile Press.