A milk jug is an object with an evident utilitarian function—consumption. However, the Turkana women cherish the milk jug as an aesthetic object. What is so special about milk and the milk jug?

The Multivocality of Symbols

Symbols serve to impart authenticity to cultural constructs, rendering them tangible, so to speak. These symbols also reflect significant structural components within a culture. These structural elements, perceived as eternal, subsequently affirm a lasting meaning to the feelings of love, ennobling them.

A symbol has the capacity to reference multiple ideas and invoke multiple feelings (Turner 1967). This capacity to hold onto multiple meanings is no different than the human self, which is the center of the physiological, emotional, ethical, aesthetic, and religious understandings and experiences of the world.

The Multivocal Symbols of Love

In the same way, symbols of love can take on many meanings, invoking multiple dimensions of love that bind humans together, providing a unified sentiment underlying human sociality. I believe that symbols of love are grounded in the memories of lovemaking and being in love.

According to philosopher Irving Singer (1984), romantic love encompasses ideals, ethics, aesthetics, sexual pleasure, passion, and ennobling qualities. Because of its multivocal capacity, a symbol of romantic love can index all of these.

Let’s consider how symbols of love are embodied in the culture of the Turkana people. The Turkana are nomadic pastoralists living in the Rift Valley of northwestern Kenya in East Africa.

The Multivocality of the Turkana Milk Jug

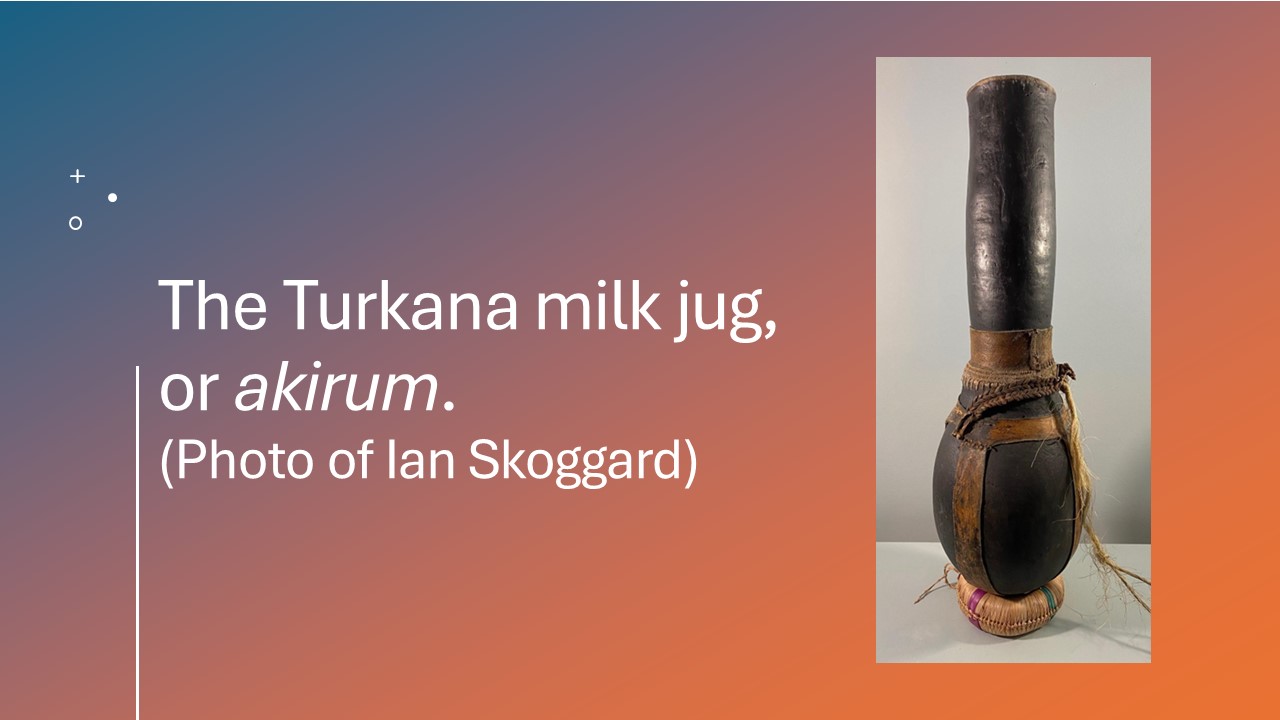

The Turkana milk jug, or akirum (see figure above), is both a utilitarian and aesthetic object cherished by Turkana women. As a common object of consumption, milk is symbolic of social relationships in bringing together spouses, siblings, and friends in relationships of consumption.

The word akirum also means “to pass down,” and as Norwegian anthropologist Vigdis Broch-Due writes, “it is a metaphor for the combined lines of descent that converge in the child from mother and father (Broch-Due, 1990, p. 99).” However, the milk jug’s most salient reference is to romantic love.

The Milk Jug as a Vulvic-Phallic Image

Two Turkana symbols of love are tiangu and akirum. Tiangu means “a wild reproducing animal.” It is also, Broch-Due writes,

a figure of speech for both human vagina and penis, conceived as linked in a single form. This metaphor creates a multiple image, momentarily eclipsing differences not only between animals and humans but also between men and women (Broch-Due, 1990, 54).

For the Turkana, according to Broch-Due,

The person is not a unitary, bounded entity, but plural and permeable (ibid.).

The Turkana milk jug is a symbol of tiangu. Its shape has the properties of both genders: the phallic-shaped neck and the rounded bottom of the jug, signifying breast, womb, or vagina. Broch-Due writes,

its form copies the procreative organs of the spouses in single form” (Broch-Due, 1990, 99).

The milk jug is an example of a vulvic-phallic image discussed by anthropologist Wilson Duff (1981) for Northwest Coast art. Such vulvic-phallic images invoke the feelings associated with lovemaking and being in love.

Anthropologist Michael Jackson expresses the unbounded feelings that come with making love:

That night, writing in my own diary, I thought again of the penumbral regions where we lose sight of ourselves–the bush, the wilderness, the other–and how natural it seems to understand this experience in sexual terms, since it is in making love that our ordinary sense of boundedness and being is overwhelmed and momentarily lost before we return to ourselves once more, renewed (Jackson, 2006, 158).

You can learn more about cultural symbols of love and sex from Ian Skoggard’s video talk on “Representations of the Love Act across Cultures”

References

Broch-Due, V. (1990). The bodies within the body: Journeys in Turkana thought and practice [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Bergen.

Duff, W. (1981). The world is as sharp as a knife: Meaning in Northwest Coast art. In D. N. Abbot (Ed.), The world is as sharp as a knife: An anthology in honour of Wilson Duff (pp. 209-224). British Columbia Provincial Museum.

Jackson, M. (2009). The palm at the end of the mind: Relatedness, religiosity, and the real. Duke University Press.

Singer, I. (1984). The nature of love, Vol. 2 – Courtly and romantic. University of Chicago Press.

Turner, V. (1967). The forest of symbols: Aspects of Ndembu ritual. Cornell University Press.