As I described in my previous article, modern cultures motivate us to live and love authentically. This entails being genuine and forthright with oneself and others. This also entails accepting accountability for your errors. Such an authenticity can be challenging, and it can hurt. Why so?

Why Authenticity of Feelings Explain Why Love Hurts

Sociologist Eva Illouz presents the concept of “authenticity” and explains why love hurts when we experience authentic feelings in our love relationship. Eva Illouz shows how cultural evolution transformed performative love into authentic love.

This cultural transformation was evident even in the early 20th century, when courtship appeared to become increasingly more private and less of a collective process.

In my recent article Towards a Regime of Authenticity. Reading A Room with a View through the Lens of Contemporary Romance Scholarship, I suggest that E.M. Forster’s A Room with a View (1908) is one of the first modern romantic novels to display the emergence of the regime of authenticity.

The narrative of the novel makes this important turn visible. Let’s look how A Room with a View illustrates the transition from performative love to authentic love

Protagonist Lucy Honeychurch falls in love privately, thoroughly avoiding courtship as a process a young woman would go through from a position of encasement within familial protective relations.

The Older Regime of Performativity in A Room with a View

In A Room with a View, we see numerous clues of the older regime of performativity, as well as clues of the emerging one (authenticity) at play. Lucy, a young English girl from the upper class, is used to rely heavily on other people’s opinions in all kinds of matters, from artworks to human character. Her autonomy of thought and action has never been cultivated and/or encouraged.

It is apparent, for instance, how much her mother’s opinion of her fiancé matters to her. Lucy eventually decides to break off her engagement to him when she sees him through the eyes of the members of her family. The fact that George Emerson, the man she falls in love with, wishes Lucy to always be her own person, plays a big role in Lucy’s final decision.

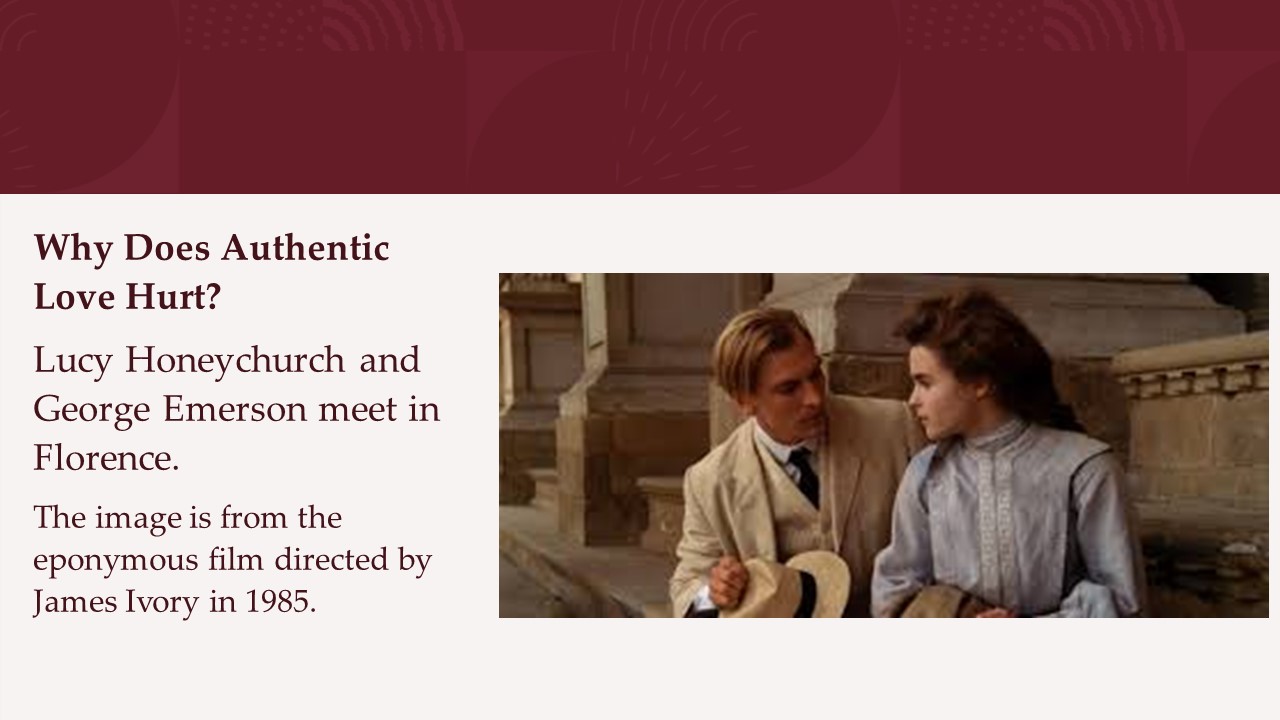

What Happens When Lucy Meets George in Florence?

When Lucy meets George Emerson in Florence, she feels something for him almost immediately, but instead of submitting this feeling to the established (even if surely changed since Austen’s time) practice of courtship and the collective judgement of her loved ones, she denies it at first, then keeps it to herself, getting deeper and deeper into a muddle she will be rescued from, at the last minute, by George’s father, who will force her to turn, perhaps for the first time, her gaze inwardly, leading her along the path of revealing her feelings to herself and to him. Ultimately, she will make her decision based on those feelings.

Lucy takes an important step towards this new episteme of romantic relationships, one certainly more familiar to us. But Lucy was not expected to choose alone, at least not entirely. The main problem with Lucy’s engagement to George, therefore, seems to be the fact that Lucy goes through a fundamental process, one that has been, for a long time, regulated and codified, all alone, depriving her family and her mother especially, of the role she was expected to play.

Soundtrack from the 1985 James Ivory film “A Room With A View” and the episode with the Kiss in “A Room with a View” from the film

Why Did Lucy Act This Way?

Lucy’s behavior is not an act of conscious rebellion against the older order of things; she very clumsily follows a deeper and unacknowledged necessity to choose independence and authenticity over conventions. But her mother calls this ‘hypocrisy.’ Lucy has been duplicitous because she has made perhaps the most important decision of her life and the last one in which her mother was to be involved, alone, independently of “the web of one’s commitment to others.” (Why Love Hurts, 28-29).

Therefore, even if Forster creates a happy ending that formally adheres to the rules of romantic fiction—Lucy and George get married—he also adumbrates the world of existential isolation typical of the current condition. Lucy “pays” her independence and happiness with a (momentary?) estrangement from her mother and brother.

Why Can Freedom of Choice Hurt?

Love hurts because the current regime—authenticity—gives individuals much freedom in their choices. But it also places a heavy dose of pressure on them. They are required to know themselves well and what they want at all times, constantly questioning their true (authentic) feelings. Also, the current regime of authentic love requires each of us to choose without help. Family members are certainly not supposed to help in choosing one’s partner. This makes us, again, free and autonomous in our choices, but also, possibly, isolated and lonely. Love hurts because it requires all this hard work. In the authentic regime, individuals are expected to carry it out individually, not collectively.

References

Illouz, E. (2012). Why love hurts: A sociological explanation. Polity.